I am proud to use the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method. In the 25 years I have taught in New York City schools, I have seen the deep and powerful effect of this method on students’ lives. Never has the need for it been more urgent. In halls and classrooms it is common to see suspicion, hate, and mockery between students of different races and cultures.

Aesthetic Realism can end prejudice because Eli Siegel, its founder, understood the cause: Contempt, the “disposition in every person to think we will be for ourselves by making less of the outside world.” (See www.aestheticrealism.org)

Though I saw myself as “liberated,” I was prejudiced against other people simply because they weren’t me! When I began to teach, I contemptuously presumed my students didn’t have it in them to do as well academically as I had, and unknowingly I was out to prove this. In my first teaching job at an all-boys Catholic school in the South Bronx, under the guise of “high standards,” I gave work that was too hard, for which my students had not been prepared. The first quiz had thirty-three difficult questions and all my classes failed. I was distraught, yet I told myself triumphantly, “We weren’t like this in high school.” I then made the tests easier—not out of good will, but with contempt for the students’ possibilities. My patronizing attitude brought out anger and contempt in my students, and lessons were interrupted by loud talking, paper airplanes, and spitballs. I was lucky it wasn’t worse. I didn’t like myself because I was unfair and often felt nauseous, praying to get through the day.

Thank goodness I heard criticism of my scornful, superior attitude! In classes on the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method, I was given assignments—such as: write something every day that a student in my class knew which I didn’t know and from which I could learn. This immediately made me respect my students more. I told them what I was learning, including the criticism of me for making my lesson plans so obscure no one could understand them; and these young men were kind: they wanted me to be better.

I tell about a lesson I gave at a high school on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As in other schools, anger often showed itself intensely between people of different ethnic backgrounds. There were fights in the cafeteria and parking lot. Often after school police cars were outside to prevent fights as students left the building. Students showed prejudice when announcements were made over the loudspeaker in English, Spanish, and Chinese—they would laugh and mockingly imitate the languages different from their own.

Students in my biology classes were Latino, African-American, and Asian. Some lived in dangerous places where they were looked down on because of their accent, lack of money, or skin color. I was proud to tell them how angry I am at our cruel economic system, and also to express the shame that I have, as a white person, for the injustice they have met, and my gratitude to Aesthetic Realism for enabling me to be against prejudice, including in myself.

Through the Study of Viruses, Prejudice Is Opposed

My lesson about viruses was part of a larger unit on disease. Not only were my students successful in learning the subject, they also were able to look scientifically at prejudice in themselves—and oppose it. I told them that our purpose in studying viruses is the same as the purpose of all education: “to like the world through knowing it.” The great educator Eli Siegel explained the one basis on which we can honestly like the world without ignoring what is painful or ugly: “The world, art, and self explain each other: each is the aesthetic oneness of opposites.” Scientists have studied viruses—what diseases they cause, how they are spread—to learn how to combat them; and my students saw that this purpose puts together opposites: going toward something through knowledge, as a means of being accurately against it.

The word “virus” comes from the Latin, meaning “poison.” Viruses are parasites; described in our textbooks as “nature’s muggers.” I read to the class from The Body Victorious by Lennart Nilsson:

No virus exceeds a few millionths of a millimetre in diameter. To a virus, even a bacterium is as large as a house is to us, and the human cell is like a whole city block. A single red blood cell is about 150 times as large as an ordinary virus.

Though tiny, viruses are extremely powerful: they can fell an organism or person billions of times larger than themselves.

Students were excited to see that fearsome viruses are made up of the same opposites — power and delicacy, large and small — that are elsewhere in reality. I asked: “What other things in the world are very small but very powerful?” Robert de la Cruz (names of students are changed) said, “An ant—it can carry things one hundred times its weight.” Lorraine Johnson said, “A microchip from a computer can store thousands of pages of information.” I asked, “What about a word?” Jamal Coleman said, “I’ll tell you a powerful word: love.” Everyone said “Yeah!”

Viruses and Contempt

We learned that viruses, unlike bacteria and other living things, are not cells; they have no nucleus, cytoplasm or cell membrane. They consist of a piece of nuclear material, DNA or RNA, surrounded by a coat of protein, and they can’t reproduce on their own. A virus either remains inactive, or invades a living organism and uses the cells of that organism to reproduce itself, and in the process it destroys the cells. As we learned this, something which can be so dangerous to life my students found very interesting—and this is on behalf of respect, not prejudging it with disgust and fear.

I read them Nilsson’s description of a T-4 virus invading a cell:

After about twenty minutes, the cell bursts and a couple of hundred new virus particles pour out. Each one of them can infect an additional cell. Every twenty minutes, infected body cells thus shed thousands, and soon millions, of these particles….And in twelve hours an unprepared immune system cannot possibly mobilise countervailing weaponry: we fall ill.

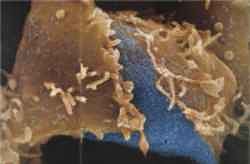

We were amazed at the speed with which a virus can reproduce. I showed a dramatic photograph by Nilsson of an invaded cell, so full of viruses that after 9 hours, it burst. Students commented that, considering the power of viruses and that they are found in water, air, soil, on dust, in food, it is amazing we don’t get sick more often.

We were amazed at the speed with which a virus can reproduce. I showed a dramatic photograph by Nilsson of an invaded cell, so full of viruses that after 9 hours, it burst. Students commented that, considering the power of viruses and that they are found in water, air, soil, on dust, in food, it is amazing we don’t get sick more often.

The reason is that our bodies produce proteins called antibodies that prevent the virus from attaching to our cells. Thousands of antibodies are produced every second. Another way our bodies defend themselves is with interferon, a substance released by infected cells that alerts neighboring cells to the presence of the virus. These neighboring cells then produce a protein that keeps the virus from multiplying within them.

The class was thrilled to learn about this fight between healthy cells and the virus, and see it is related to an ethical fight in people. We saw that what the virus does is like what we can do: want to take over and run other people, without caring who they are or what they feel. And while viruses are harmful, through studying them scientists are learning to oppose them. In the same way as a virus can be examined under an electron microscope as a means of fighting it successfully, we can look at our contempt—from which all prejudice and bigotry come—with the same scientific rigor, and oppose it.

The class eagerly discussed ways people try to build themselves up by making less of someone, and I respected their forthrightness. Jay Randall said that children used to make fun of him because he grew up in a foster home; and one day when he was ten he punched another boy for this. While he felt tough at the time, he wished he had “expressed himself in a more eloquent way.” I asked, “Are you saying you shouldn’t have met this person’s unkindness by having contempt yourself?” Jay said with a smile, “Yes!” Luis Diaz told about coming to school with a new haircut and new clothes, and feeling superior to a friend who didn’t have nice clothes. Later he was sorry. He saw that using one aspect of a person—clothing—to judge the whole person is inaccurate, unkind, and a form of prejudice. Jason Miller told how, the day before, while sitting in the cafeteria feeling bored, he began dissing people around him. By the time he got home, he said, he felt really bad.

Students listened to one another with great interest. They saw that their contempt had weakened them—that they didn’t like themselves for having it.

Vaccine: the Harmful Made Useful

I asked the class how many students had had the measles. Few hands were raised. “Why do you think that is?” I asked. Lisa Morris said, “I had a vaccination for measles.” I asked if they knew what was in that vaccine. “It is made of the measles virus itself. The virus is treated chemically so that it is too weak to give you the disease, but strong enough to enable your body to recognize it and produce antibodies to protect you if you become exposed to the actual measles virus.” Students were excited to see the opposites: the thing that causes a disease can, in another form, prevent our getting it. “Do you think this shows that knowing a hurtful thing is a way of being against it?” I asked. Yes! “This goes for contempt too.”

The effect that these lessons had was profound. My students learned. Not only did they do well on the exam, but students who had made fun of each other became kinder; they listened to each other with new respect. I was moved to hear a Chinese student ask some Latino students to help him choose an American first name for himself; they all decided on “Peter.” And something that is practically unheard of in high schools—students of different nationalities volunteered to telephone each other if someone wasn’t in class, to find out if that person was all right.

I was very moved by what my students wrote at the end of our study of viruses. David Zeng, a young man who was in Special Education classes for many years, wrote:

This study proved to me that contempting anyone else would not make me bigger. No matter what kind of color [people] are, they are the same human as me.

And Rafael Martinez wrote:

I’ve learned that everyone is equal, and no one should put someone else down just to make yourself feel better.

When the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method is known throughout our country, not only will young people learn science eagerly, but prejudice in our schools, so terrifyingly rampant today, will end!

Sally Ross writes articles and presents workshops on the success of the Aesthetic Realism Teaching Method at professional conferences and colleges.