Dear Unknown Friends:

We publish here the great essay “Art as Criticism,” by Eli Siegel. Written in the 1950s, it is an exemplification of the fact that Aesthetic Realism has explained what beauty is, and what the human self is. In the essay, Mr. Siegel is writing about the thing every person needs and wants most, however much a person seems to go after something else. That most needed thing is criticism.

It’s true, people want flattery, to be told they’re okay—in fact, wonderful. And psychologists are advising people that is what they need: to be “accepted” and “accept” themselves as they are. But Aesthetic Realism shows—and I’m immensely grateful to have learned this—that no amount of praise or “acceptance” will ever have us like ourselves. We want authentic criticism, criticism with enough knowledge in it.

The Fight, Explained

Aesthetic Realism is the criticism with enough knowledge in it. It explains that the big, constant fight in every person is between two desires: our desire to like the world, see it justly; and our desire to have contempt for what’s not ourselves as a means of giving a false value and superiority to ourselves. We want that first desire encouraged, because it’s the one thing we can respect ourselves for. And we want desperately to have the other tremendous desire in us, our contempt, criticized: criticized keenly, deeply, richly, because it has held up our lives, interfered with our minds, interfered with love, made us dislike ourselves. This thirsted-for education, the authentic oneness of encouragement and criticism, is Aesthetic Realism.

The current issue of TRO is being published during the holiday season, when, even more than other times of the year, people are giving and getting approval. Yet always, we need to approve exactly, and condemn exactly, and we need to be seen exactly. Because this does not happen, people are angry and empty—anytime, and in the holidays’ aftermath.

Aesthetic Realism Consultations

When a person begins to have Aesthetic Realism consultations, the consultants ask him or her a question that Eli Siegel asked in Aesthetic Realism lessons: “What do you have most against yourself?” This mightily kind question and others, and the education from which they arise, have a person feel what people for centuries have wanted to feel: I’ve met that which respects me enough to be interested really in what I think of myself! I’ve met that which respects me enough to see that I can’t like myself for being unjust! I’ve met education that fights for the best thing in me, and explains what that best thing is: my desire to like the world!

The Critical Criterion

Eli Siegel is the philosopher who has stated the enduring criterion for criticizing anything—a painting, a poem, a marriage, our motives. The criterion is in this Aesthetic Realism principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves” (Self and World, p. viii). That critical principle is also the biggest praise of us, because it says we are deeply asking to be nothing less than art.

I consider Mr. Siegel both the greatest critic of literature and art, and the greatest, kindest critic of people. It is the honor of my life that he was a critic of me, in Aesthetic Realism lessons. With enormous kindness and clear logic, he had me see about myself what is in these lines from his poem “Afternoon,” about Mr. Bulwer:

Happy, happy Mr. Bulwer—

That you are more than you show,

More than you talk,

More than your tone.

Happy, happy Mr. Bulwer

That

You are more than you chose to see.*

How people are more than they have chosen to see, is what they want to learn about themselves, and what they can learn in Aesthetic Realism consultations.

—Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism

Chairman of Education

Art as Criticism

By Eli Siegel

For adoration seasons change,

And order, truth, and beauty range,

Adjust, attract, and fill:

The grass the polyanthus checks;

And polished porphyry reflects,

By the descending rill.

—Smart, A Song to David

When an artist paints a picture, he is saying that the thing he has painted is good for himself and good for other people. Every picture, then, is a criticism of the world, or things, and is a favorable criticism. The painter is saying that if this and this were seen right, and I am trying to see it right, this and this would have a good effect on people, and would praise the meaning of the world. Every painting, then, is a work of criticism and devotion.

Art is criticism and devotion. Criticism, however, is an accurate interaction of rejection and acceptance. It has been given to man that he be able to like and dislike reality; be for it and against it; indeed, to be a man means that you are always in the midst of antagonism and welcome. The devotion that is art arises from a true relation of antagonism and welcome, not from a superficial, incomplete welcoming. Only he who has found the universe tough, grudging, or puzzling; or God not so bland, granting, placid, can come to true devotion. Art is the criticism which is also love.

The Artist Asks More

Matthew Arnold has said that poetry is “a criticism of life”; and this is true of poetry, as it is true of all art. The world asks that it be judged, known; known, judged—so that it can be liked. All art has a oneness of discontent and pleasure. The artist asks more of an object, even while he accepts it; he asks more of it, because he can accept it. The artist shows a thing more as it is, by seeing it more as it does not seem to be usually. Of every object the artist says: I can like how I see this object, and therefore, since the object has given rise to a thought or way of seeing I like myself for, the object has been a cause of good.

The world cannot be seen as good until it is criticized; and art is the criticism, and, through criticism, the loving acceptance of the world. Rejection given form, in art, is acceptance. Rejection can take a beautiful form, but once it has a beautiful form, the rejection is beautiful itself. As beautiful, it can be accepted; is acceptance. Another way of putting this matter is: Art is that part of life which makes it beautiful by showing that the criticism of life can be beautiful.

Acceptance & Rejection at Once

All art says that things are interesting, and to say that something is interesting is on the side of praise. Further, art says that a thing, happening, or situation can be so presented that, seen as the artist saw it, it can do mind good. The artist is here, then, a defender of reality, for, after all, he paints it; he is a critic of reality, for he gives it a form arising in his mind. Great art is the utmost acceptance and rejection at once of the deepest and most immediate reality; or, great art is great criticism.

El Greco is a critic of reality in his way. His vision is his criticism. Goya is a critic of reality. Courbet is a critic of reality. But so are Rubens, Turner, and Renoir. Art as criticism consists—as it does everywhere—of three things: acceptance, rejection, change. Change itself is addition and subtraction. In painters’ terms, we add something to an object, we take something from an object, while we’re in the midst of rejecting and accepting it.

To See Is to Criticize

To see is to criticize. To see itself is an acceptance, but as we see, we dislike or reject, too. Every artist has looked for what he hated and loved. What an artist omits, is a sign of what he loves. A painting is a rich presence of what’s there and what’s left out; what wasn’t there and what was put in.

To choose, to intensify, to mute, to relate, to exclude: all these are of criticism, and all these are painters’ activities or procedures. A painter makes the world suit his idea, and his idea suit the world. As he does this, he is a critic of himself and reality. To be an individual is to criticize reality. To be an artist is to criticize reality in such a way, that the criticism is an intense acceptance.

In Art’s History

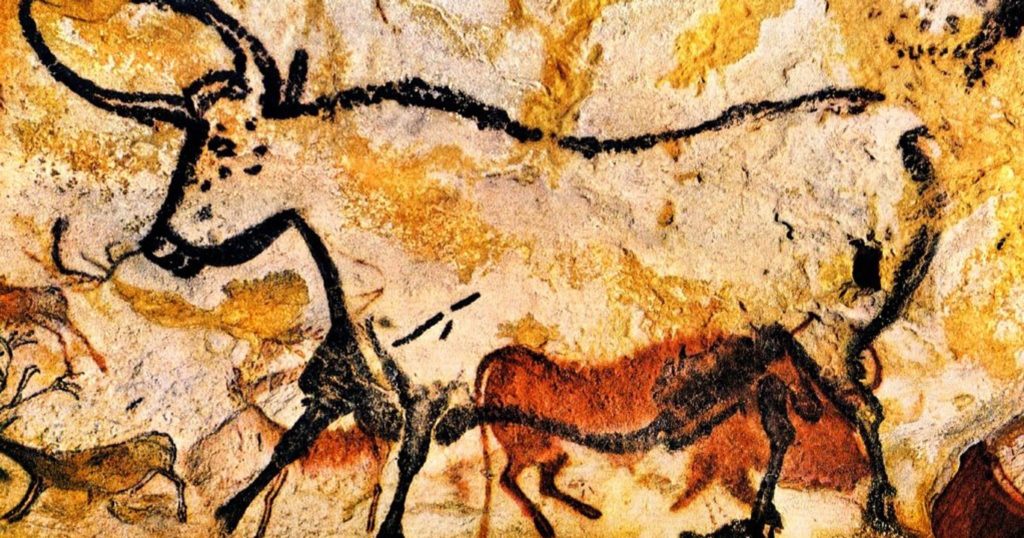

That art is criticism, can be seen in art’s history, I use Helen Gardner’s Art through the Ages (ed. 1936) to show that art has always been criticism, a criticism that went for acceptance through form—for adoration through form—as Christopher Smart might have said. —Ms. Gardner is writing (p. 10) of the primeval paintings found in the caves of Southern France:

Each painting reflects the keen observation of the hunter-artist, and especially an extraordinary memory for instantaneous poses, whose accuracy has been proved and hardly surpassed by the motion-picture camera of today. Yet this observation was of the selective type. It saw and recorded only those essential aspects which interpret the appearance and character of the animal, its grace or awkwardness, its cunning or dignity.

I think in this passage one can find that acceptance through criticism I have been presenting. We have that omission, that dealing with “essential aspects,” which are part of the acceptance-and-rejection-oneness in art. This more and less, addition and subtraction, we have in all art. But more and less, addition and subtraction, as chosen by mind are criticism.

About Goya

In a passage about Goya (p. 477), Ms. Gardner presents the Spanish painter as leaving out and heightening at once. It should also be remembered that while Goya as satirist opposes, as person interested, he includes. When Goya gave form to the things he satirized, he was giving a goodness to them. Ms. Gardner is commenting on Goya’s Why Hide Them?:

Goya’s draftsmanship is as incisive as his satire is biting. With a few economical lines and a dynamic patterning of black and white he has set forth the significance of the situation with amazing lucidity and startling power.

Goya can be described as a lusty satirist. His lustiness, his joy, are saying, This is good; his satire, This is bad. His form makes a one of his adverseness and his favor; his form is that which, criticizing reality, accepts it, too. When you put two of Ms. Gardner’s phrases together—“incisive as his satire” and “with amazing lucidity and startling power”—you can feel that negativeness and positiveness, that antagonism and exultation, which can make for criticism as art, art as criticism.

Here Is Degas, Criticizing

Here is Degas, as described by Ms. Gardner (p. 663), criticizing with his eye and self something he sees, and changing it into a thing of style:

Whatever it happened to be, Degas saw it as clear line and pattern caught in some casual moment. The awkward pose of a ballet girl tying her slipper became a sensitively realized decorative motif in an asymmetrical composition whose first impression is as casual as the theme.

When someone sees “the awkward pose of a ballet girl tying her slipper” and changes it into “a sensitively realized decorative motif,” whatever else he is doing, he is criticizing: his eye is criticizing, while it is blissful. To change a locomotive into a pattern of curves, straight lines, and somber blacks and greys is at once to see more and less in the locomotive. It is to make the locomotive something lovelier than ever, perhaps, while altering a customary notion. It is the criticism of imaginative transmutation and satisfaction.

More General, More Personal

The criticism which is art has made a personal thing more general, and a general thing more personal. Either way can make for loveliness. Ms. Gardner, dealing with the statue of Augustus in the Vatican, writes (p. 199):

But the face does not characterize Augustus in detail, as does the head of the Unknown Roman. There are no individual lines to indicate personal idiosyncrasies. It is rather a generalized type distinctly reminiscent of Greek work.

An artist criticizes reality by making it more “personal” or more “general” than it customarily seems. It comes back to the fact that to see is to criticize; for to see is to accent and mute, include and leave out, add and subtract. In art, what the eye and self do is for the honor and full truth of reality; in what isn’t art, the eye can change reality out of fear, and in a manner dishonoring it.

The Artist’s Way

The artist’s way is the utmost judgment, scrutinizing, questioning of reality as a means to an honest like, admiration, acceptance, adoration (again, Christopher Smart) of reality. We can see this critical alertness with deep assurance in the following statement (p. 405) of Ms. Gardner about Michelangelo:

Although all [the Nudes] serve the same decorative purpose, still they are very different, each, perhaps paradoxically, a more or less realistic rendering of the human figure and at the same time an expression of a definite inner state of mind.

Michelangelo, in other words, accepts what he sees while with his “inner state of mind” he criticizes what he sees, adds to it.

Something to Praise

Michelangelo, because he saw, was a critic of reality. Because he was an artist, his criticism—including what this criticism rejected—became love through form. Reality, criticized, given form, became more than ever something to be for, something to praise honestly.

*Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana: Poems (NY: Definition Press, 1957), p. 88.