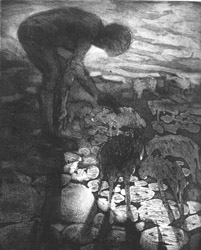

There is a power and beauty in the work of the noted American printmaker Chaim Koppelman that made his recent exhibition at the Beatrice Conde gallery unforgettable. The great variety of works from over four decades included not only some of the most masterful etchings and aquatints I’ve ever seen – such as Gentleness, Combat, Napoleon Entering New York – but also lithographs, and pastels. The artist’s works are extraordinary dramas of dark and light; his blacks have a breathtakingly rich, velvety quality and his whites are so intense and luminous, you feel matter glows. “I want to show,” he writes, “the ethical drama of good and evil in ourselves, evocatively, starkly, subtly, humorously, and with mystery.”

Chaim Koppelman—Etching/Aquatint

Courtesy of the Artist

Chaim Koppelman—Aquatint

Courtesy of the Artist

Collection of the

Museum of Modern Art

Chaim Koppelman is one of the earliest artists to see the truth and value of the philosophy of Aesthetic Realism for art and life, beginning his study in the 1940’s with its founder Eli Siegel, the great American poet and critic. In the exhibition announcement the artist writes:

I am grateful to Eli Siegel…for teaching me and the world the enduring criterion for judging what is beautiful in art and good in life: “All beauty is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” Continuing to study and teach this mighty principle is an honor and a pleasure; it has given coherence to my life, made me more imaginative, deeper, and a kinder person.

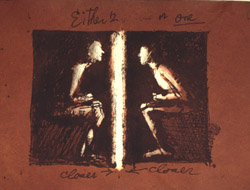

An incisive, often satirical critic of humanity, Chaim Koppelman is never bitter nor cynical; he is kind – and we see it in the form, the technique – as in his dramatic colored etching of 1991, Closer and Closer. Within a vivid reddish-brown rectangle is a smaller deep brown rectangle, divided by a glowing vertical band of light which illuminates two seated figures in profile, leaning towards and looking intently at each other. The tension between them is made vibrant by the light which not only separates their forms, but through its intense luminosity, also joins them, and the figures become, as the artist writes beneath them, “closer, closer.”

Chaim Koppelman—Colored Etching

Courtesy of the Artist

Philadelphia Museum of Art

Commenting on this work, he says:

I was trying to make visual the deep idea I learned…that the self of every person has two aspects, one narrow, wanting to like only itself, and the other wanting to be fair to all that is outside itself – and the aesthetic and ethical job of our lives is to see these two aspects…as one.

Another moving work is “Over Brooklyn,” from the 1975 suite of five color lithographs titled Closeness and Clash in Couples and Domestic Life, for which the artist received a CAPS grant. It puts together, through form, the intimate and wide, everydayness and mystery: opposites people, families, want to put together in their lives. In the night sky, floating above the silhouette of a small apartment building, an elderly couple sit at their kitchen table, their forms illuminated by a glowing light bulb above them that has taken on the quality of soft moonlight. There is geometry – the abstract world – in their midst as the artist relates the rectangular plane of the table top to the surprising diagonal plane of bright green grass that supports the dark night scene. The persons close to us, perhaps our parents, whom we so often take for granted, he shows can be seen with wonder, mystery, and loveliness as they are lifted up into the sky, into the light!

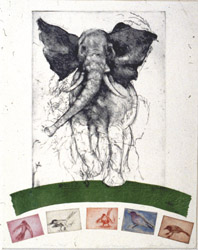

In the delightfully engaging The Kind Messenger, a hand-colored etching/collage, we see a massive, lumbering elephant, exquisitely drawn, with ears flying buoyantly, bounding towards us, over a painted arc of bright green.

Chaim Koppelman Hand—Colored Etching/Collage

Courtesy of the Artist

And beneath this is another arc composed of five small collaged rectangles, each containing an etching of a bird with a delicate watercolor wash. These tiny birds seem to support and lift the large, energetic mammal. The weighty and the lightsome take on a meaningful, surprising, and joyous relation! “Koppelman [is] an innovator,” wrote critic Sylvan Cole, “not only technically, but in the scope of his subject matter, the depth of his seeing.”

Some of that great depth can be seen in the artist’s courageous work opposing the brutal Vietnam war. His protest, writes Ralph Shikes in The Indignant Eye, “springs from the art and is not superimposed upon it.” “Our Injustice, Vietnam,” a luminous silvery-black embossment of 1970 depicts in relief the naked bodies of babies hanging from hooks across the top of the print. Yet there is motion, vigor in their forms. On that dark yet glowing surface, the artist makes a one of the unbearably heart-wrenching and the beauty of form.

“Babies,” he wrote, “represent the life principle in the world and ourselves. I wanted these babies to persist in their liveliness even as horrible things are done to them, even as we try to kill them.”

A poem Chaim Koppelman includes on his exhibition announcement, which I think is great, is Eli Siegel’s The Print – “It gets to the heart,” he writes, “of what has impelled me and other printmakers with beautiful precision, depth and music.”

The Print*

Can dark and light

Show wrong and right?

–And round and straight

Show love and hate?

–And dim and clear

Show hope and fear?

Chaim Koppelman, a member of the National Academy of Design and a former President of the Society of American Graphic Artists, represented the US in Documenta II, in Kassel, Germany. He is the recipient of numerous awards, and many of his distinguished prints are in the collections of major museums here and abroad. He teaches printmaking at the School of Visual Arts and is a Consultant on the faculty of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation where he teaches the class Art of Drawing: Surface and Depth, and teaches artists in Aesthetic Realism consultations with the trio The Kindest Art. As an artist, grateful to have studied with The Kindest Art, I know there is nothing greater for a person to learn than that art – in its purpose and technique – has the answers to the deepest, most immediate questions of our lives.

* Eli Siegel, Hail, American Development, Definition Press, NY, 1958.

The Koppelman exhibition was at the Beatrice Conde Gallery, 529 West 20th St., New York City, from April 20 to June 3, 2000.