Aesthetic Realism teaches that a man’s hope to respect the world makes him kind, proud, smart, strong, and his hope to have contempt—defined by Eli Siegel as “the lessening of what is different from oneself as a means of self-increase as one sees it”—weakens him, makes him cold, cruel, ashamed, stupid. Growing up, I used the confusion and pain I saw in my parents to have contempt—feel I was superior, more sensitive and sensible. A tremendous thing happened in my life when my father, Sam Koppelman, attended an Aesthetic Realism lesson with me, and Mr. Siegel taught us how to be kind to one another.

by Chaim Koppelman

I used the fact that I was more educated to be cold to my father. Sam Koppelman had worked in the leather business and later as a tailor in a factory. Yet even as I said I was for “the working man,” I looked down on him. I was cold to what he felt when we lost our home during the Depression because he didn’t have enough money to pay the mortgage. Meanwhile, I acted very concerned about the suffering of the Chinese people 6,000 miles away because Japan had just bombed Shanghai.

Mr. Siegel told me, “Any way or action making less of the world, of others, be it in the family, in art, or in eating, is bad. It is self-love. There is a kinship in fascist cruelty and self-love.” He said to Sam Koppelman, “A person wants to hear things that show the other person sees him from the inside. Has anyone seen you the way you see yourself?” “No,” my father answered, “it has never happened before.” For the first time in his life, he was being seen, by Mr. Siegel, the way he saw himself.

Mr. Siegel said, “Every father and son want the same thing—that they talk as if they are two persons who have the same problems. Most fathers and sons, when they talk, feel there is a poker inside. Not giving in is the family game.” He asked about me, “Is Hi stiff with you?” And Sam Koppelman answered, “He doesn’t listen to me, so I don’t listen to him.” Mr. Siegel then put into words I love what all fathers and sons desperately need to say. He said a son should say, “Dear God, I didn’t try to understand myself and my father.” And a father should say, “Dear God, I didn’t try to understand myself and my son.”

He described what worried my father as he thought about himself. “Do I mean something to the world? This is the first question in feeling useful. Not how much money you make or don’t make. What do you want to fight for, Mr. Koppelman?” Sam Koppelman answered, “A better world.”

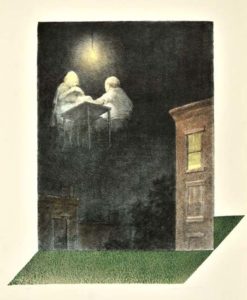

This was a revolution in my life for which I am unboundedly grateful. This wasn’t the way I had seen my father! I was supposed to be the idealist in the family. I was the one who worked to have a better world. I saw Sam Koppelman wanted what I wanted. We, father and son, were being so kindly known and encouraged by Eli Siegel, the greatest critic in history. Through what we learned, for the first time we were able to sit at the same table and have enlivening conversations without getting into ego battles that left us both drained. I also began a series of paintings about fathers and sons in Greek mythology. The family became an important subject in my work.

I have had the tremendous good fortune everyone should have: I have studied the kindest philosophy in the world and now have the great honor to teach other men what I have learned—Eli Siegel’s great Aesthetic Realism principle: “All beauty is a making one of opposites and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”

Chaim Koppelman is an artist, a consultant on the faculty of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation in New York City, a member of the National Academy of Design and teaches at the School of Visual Arts. He began his study of Aesthetic Realism with its founder, the American poet and critic Eli Siegel, in the early 1940s; and his award-winning prints are in major museum collections here and abroad. This article is based on a paper given at an Aesthetic Realism seminar.