For over a century, Beatrix Potter’s art, her wonderful imagination have affected children and adults all over the world. There’s hardly a person who doesn’t know The Tale of Peter Rabbit! Her pictures and stories, while charming and delightful, are also deep — and they show something vital and thrilling about imagination which every person, every parent, every child needs to know.

As an artist and teacher I’ve come to love and value her work even more through my study of Aesthetic Realism, the philosophy founded in 1941 by the great American poet and critic Eli Siegel. I learned that there are two kinds of imagination in every person: good and bad. In “Imagination, Reality, and Aesthetics,” a chapter from his book Self and World, Eli Siegel explains:

The difference between the imagination of art and the imagination of everyday life is that where in art imagination serves to show the self by showing the world, imagination in “life” is used to make the self comfortable, without necessarily showing it.1

It is crucial for us to be able to distinguish between these two kinds of imagination. And Beatrix Potter’s work can be so useful in seeing this. The imagination of art shows the world truly because it is fair to reality as an aesthetic structure of opposites. “All beauty,” Mr. Siegel stated in this landmark principle, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.”2 There is beauty in Beatrix Potter’s work because she put opposites together — fact and wonder, the ordinary and strange, known and unknown. And only because she wanted to see exactly and be deeply affected by things did she come to a style unmistakably her own, showing who she was by showing the world truly. Aesthetic Realism teaches, for the first time in history, that we need to learn from art — including the art of Beatrix Potter — to be proud of how we use our imagination.

Our deepest hope, the purpose we were born for, I learned, is to like the world by using our mind, our imagination to see other people and things fairly. But we also have another hope — to have contempt, which Mr. Siegel defined as “the addition to self through the lessening of something else.”3 It makes for imagination that is hurtful. We hide — we don’t want to see what is true or be honest about our own feelings — and think we are making ourselves comfortable by feeling “I can change any fact I want, see any person or thing in a way that suits me to make myself superior and glorious.” It is this ever-so-ordinary use of imagination that makes a person — young or old — ashamed, and is the cause of boredom, depression, unkindness. And it is imagination based on contempt that has made for the greatest cruelty and injustice in the world. The greatest opponent to contempt is art — because the purpose of art is to respect the world.

I was surprised to learn that Beatrix Potter, renowned for her charming, imaginative children’s books — such as The Tailor of Gloucester4, The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin, The Roly-Poly Pudding, was also a naturalist — studying and drawing every kind of animal, bird, insect, plant she could find. It affected me to read in Beatrix Potter, 1866-1943: The Artist and Her World this description by the authors:

[It is the] extraordinary mixture of reality and fantasy which is part of the charm of Beatrix Potter’s stories ….[Her] approach to fairy tales was a realistic one — yet she never lost her sense of mystery.5

Beatrix Potter wanted to put opposites together, as every person does, and she did so most successfully in her art. She herself wrote in a letter of 1940:

I do not remember a time when I did not try to invent pictures and make fairy-tales — amongst the wild flowers, the animals, trees and mosses and fungi — all the thousand common objects of the country side; that pleasant unchanging world of realism and romance.6

Eli Siegel’s essay, “Romanticism Is Still with Us,” has the explanation of the particular effect and success of Beatrix Potter’s work. He writes:

Reality is not denied, spurned, lessened, or rejected by Romanticism: Romanticism simply says reality is, and it is wonder; wonder is and it is real….All romanticists have tended to make reality and wonder akin, the fact and strangeness like each other; indeed, all art in some way has gone after this.7

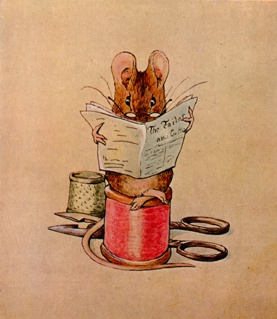

In her stories, illustrations, and her scientific studies, Beatrix Potter wanted “to make reality and wonder akin, the fact and strangeness like each other.” For example, on the jacket of her favorite book, The Tailor of Gloucester8, is a picture of a mouse, wearing black wire spectacles, sitting on a red spool of thread reading a newspaper, The Tailor and Cutter. It is charming, funny, fantastic, yet entirely sensible. There is an exactitude of observation and factuality about this drawing that makes the surprising, the strange, believable. The mouse is beautifully rendered, and though he is sitting up comfortably like a person with his feet crossed, and his hands — though we know they are his front paws — are stretched out holding a newspaper, we can see how carefully Beatrix Potter observed mice. And so importantly, with all the sweetness and charm she never leaves out the terrifying. Notice how the mouse’s pink tail curves over the fierce and menacing blades of the scissors before it comes to a rest near the spool. And there is a sense of the domestic, the near, and at the same time, the world as wide, having wonder as the mouse sits near those scissors and thimble in that transparent blue space.

As a girl Beatrix loved to draw, and wrote in her Journal about:

the irresistible desire to copy any beautiful object which strikes the eye….I cannot rest, I must draw, however poor the result, and when I have a bad time come over me it is a stronger desire than ever.9

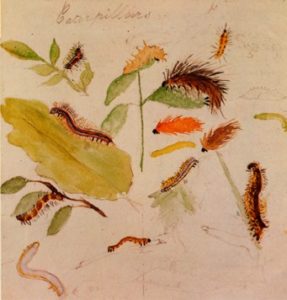

This is a drawing of caterpillars Beatrix did when she was nine — and accompanying the drawing were her careful observations about the eating habits of each.

She and her younger brother, Bertram, kept many pets whom they studied and drew. She wrote about the wonder she saw in a mouse skeleton she was mending: “I thought it a curious instance of the beautifully minute difference and fittings together of the bones.”10

Yet without knowing it she also used her imagination in a way that hurt her. Like many children, she apparently used anger and disappointment with her parents to retreat into herself. She wanted a separate world of her own, aloof from others. In The Tale of Beatrix Potter Margaret Lane writes:

Beatrix Potter had always…sheltered herself behind an immense reserve;….[and felt] a great enjoyment of the privateness of private life.11

How much was this separateness from people the very thing that made her unsure of herself?

She once confided to an American friend:

‘I’ always seem to ‘me’ to be comparatively dull, with not much to say, and with only very occasional flashes of amusement.12

In “Imagination, Reality, and Aesthetics, “Mr. Siegel describes this division in Beatrix Potter that has been in nearly every person who ever lived:

At the present time in America, wonder and matter-of-fact live on two sides of the railroad. A person behaves with groomed propriety outwardly; but in his bed, or in revery, or in just thinking to himself, there is another world. And these two worlds are seen as neighbors who need never meet. Imagination and aesthetics make for the meeting of wonder and matter-of-fact and therefore if we do not respect imagination and aesthetics consciously, we are permitting the seeds of personality disjunction to operate.13

In an Aesthetic Realism class taught by Mr. Siegel I heard the kind comprehension of this division in my life that had made me so unsure of myself. He asked: “You want to take care of your privacy, don’t you?” “Yes,” I said, “I’ve been going for that.” And he explained:

You get a value out of thinking you are secret and immune, like everyone else….The question is how much are you a part of general truth? How much do you want to be in relation to things and to the world?14

Mr. Siegel was teaching me to see what I was most hoping for — to affirm my relation to the world — and learning this has made me a kinder person, able to be proud of how I use my imagination in my life.

“Imagination and aesthetics,” Eli Siegel wrote, “make for the meeting of wonder and matter-of-fact.”15

Beatrix Potter wrote many letters to the children of her friends and relatives, one of which, written in 1902 to a little boy who was ill, Noel Moore, was to become a classic of children’s literature. I think The Tale of Peter Rabbit, translated into many languages, has affected children so much because it is against a child’s dividing the world as wonder from the world as fact. Margaret Lane writes:

All her…animals are conceived with imaginative truth, and though they are shrewdly humanized, and their stories told throughout in human terms, there is, imaginatively speaking, not a word of falsehood. We close the books knowing more about animal and human nature than we did before.16

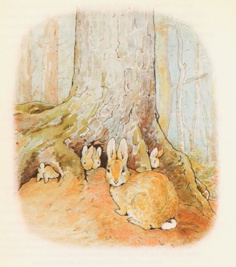

The book opens with a picture of a family of rabbits — Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-tail, Peter, and their mother — where they live in the “root of a very big fir tree.” The drawing is factual, yet the delicate pink and lavender trees in the distance seem to go into unknown space. And there is strangeness, too, in the fact that these rabbits have names and are in a domestic situation.

So, on the next page, when we see the rabbits standing up like children with their capes on, it seems perfectly natural, and we accept the strange as fact. Mrs. Rabbit tells her children they can go into the field,

So, on the next page, when we see the rabbits standing up like children with their capes on, it seems perfectly natural, and we accept the strange as fact. Mrs. Rabbit tells her children they can go into the field,

…but don’t go into Mr. McGregor’s garden: your Father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor.

Here, the terror of what happened in Mr. McGregor’s garden is presented matter-of-factly, along with the goodness of the fields and the sweetness of the drawing. Flopsy, Mopsy, and Cotton-tail went down the lane,

But Peter, who was very naughty, ran straight away to Mr. McGregor’s garden, and squeezed under the gate!19

Did Beatrix Potter want to show that a world which can be terrifying and cause pain, can also please us, and is still a world to be known and liked?

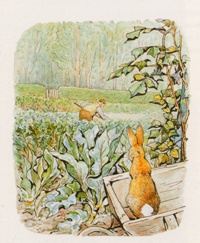

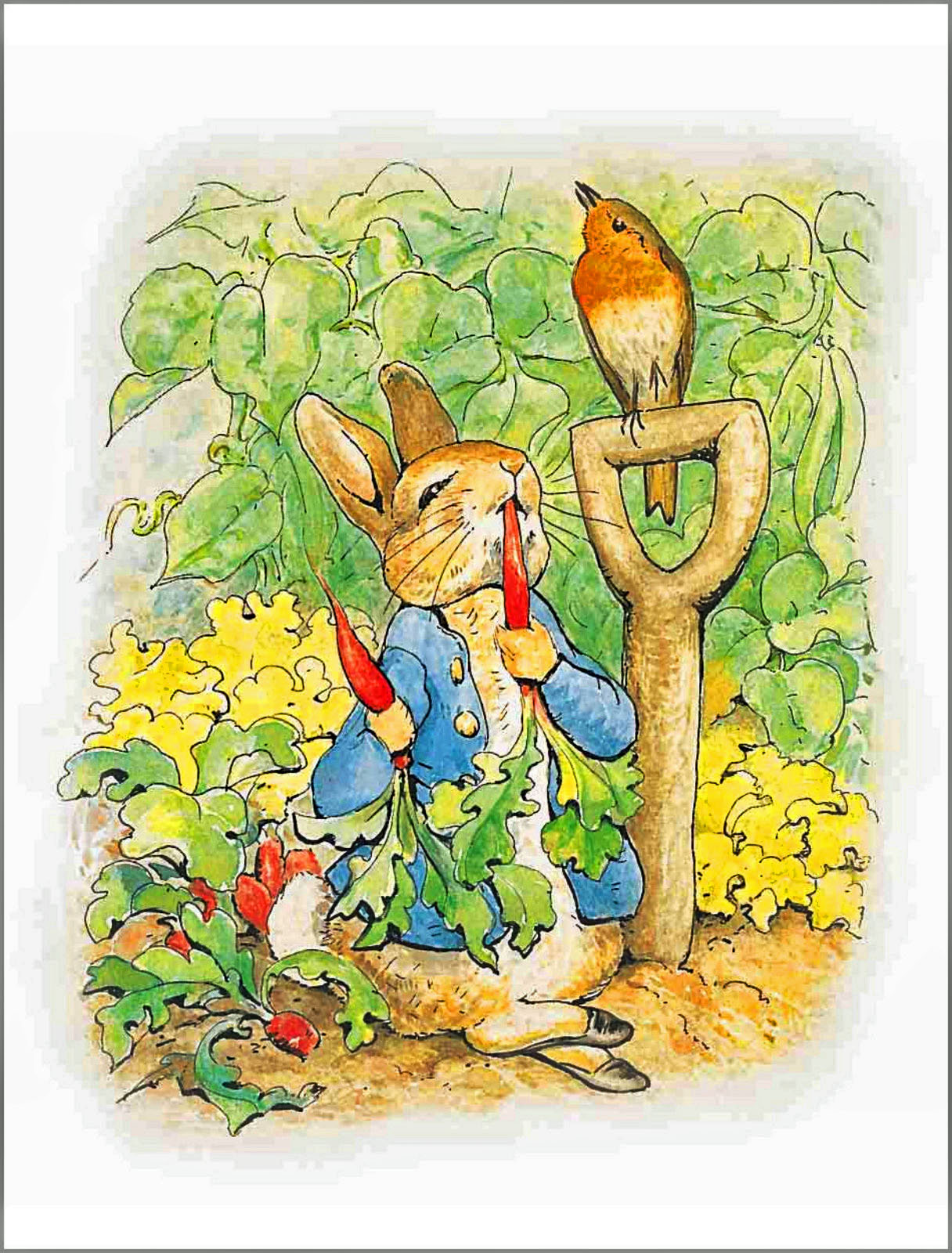

There is humor in this picture as Beatrix Potter captures the awkwardness of Peter, looking out at the garden with wonder. Peter is pleased by what he finds in the garden.

There is humor in this picture as Beatrix Potter captures the awkwardness of Peter, looking out at the garden with wonder. Peter is pleased by what he finds in the garden.

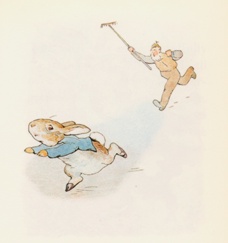

We see him enjoying some radishes. But soon he comes face to face with Mr. McGregor who runs after him with a rake.

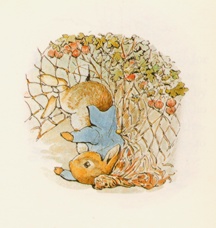

Peter, after losing “one of his shoes among the cabbages,” gets caught in a gooseberry net

Peter, after losing “one of his shoes among the cabbages,” gets caught in a gooseberry net “by the large buttons on his jacket,” and after many narrow escapes,

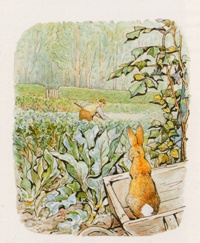

“by the large buttons on his jacket,” and after many narrow escapes, “climbed upon a wheelbarrow and peeped over.”

“climbed upon a wheelbarrow and peeped over.” We see an ordinary rabbit, with that combination of curiosity and timidity rabbits have. And Peter looks out on a world that is both fearful: there is Mr. McGregor, and hopeful — “and beyond him was the gate!” In this drawing, the relation of the precisely drawn vegetable leaves and vines, and Peter’s furry coat in the foreground, near us, and the background that gradually dissolves into the pale mist of the forest beyond, is lovely. One of the things I care for in Beatrix Potter’s work is the way the distant, unseen world is present in the immediate, factual world we see before us. Though the book is very small, there is a sense of space. Beatrix Potter carefully and beautifully places the picture in that white space that both fixes the image and also allows it to float freely as the soft, blurred edges blend into the white. Her use of the precise outlines and the soft, transparent washes of watercolor also puts together the contained and the expansive, fact and wonder.

We see an ordinary rabbit, with that combination of curiosity and timidity rabbits have. And Peter looks out on a world that is both fearful: there is Mr. McGregor, and hopeful — “and beyond him was the gate!” In this drawing, the relation of the precisely drawn vegetable leaves and vines, and Peter’s furry coat in the foreground, near us, and the background that gradually dissolves into the pale mist of the forest beyond, is lovely. One of the things I care for in Beatrix Potter’s work is the way the distant, unseen world is present in the immediate, factual world we see before us. Though the book is very small, there is a sense of space. Beatrix Potter carefully and beautifully places the picture in that white space that both fixes the image and also allows it to float freely as the soft, blurred edges blend into the white. Her use of the precise outlines and the soft, transparent washes of watercolor also puts together the contained and the expansive, fact and wonder.

“We all of us have pictures of the world in our minds — ,” Eli Siegel writes, “and these pictures are of imagination; the beauty and rightness of these pictures depend on how much we can see the world as what it is.”24

Beatrix Potter has been loved and is important as an artist and writer because in The Tale of Peter Rabbit, and in book after book, she shows that we don’t have to make up a better world. She shows deeply and surprisingly, that seeing the world we meet everyday, factually “as what it is,” will make for the wonder and excitement that is the beautiful, right imagination of art — the true, proud imagination we want in life!

Marcia Rackow is an artist, and consultant on the faculty of the Aesthetic Realism Foundation (www.AestheticRealism.org), a not-for-profit educational foundation, in New York City, where she teaches the course “The Visual Arts and the Opposites.” For information, click here.

NOTES

1. Eli Siegel, Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism (New York: Definition Press, 1981) p. 151.

2. Ibid., p. viii.

3. The Right of Aesthetic Realism to Be Known, number 1330, Sept. 30, 1998.

4. Beatrix Potter, The Tailor of Gloucester, (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1903), p. 12.

5. Judy Taylor, et al., Beatrix Potter 1866-1943, The Artist and Her World (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1987) pp. 117, 64.

6. Leslie Linder, The History of the Writings of Beatrix Potter (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1971) p. 92.

7. Eli Siegel, “Romanticism Is Still With Us” (unpublished).

8. Potter, The Tailor of Gloucester, (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1903), jacket illustration.

9. Leslie Linder, The Journal of Beatrix Potter (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1966) p. 106.

10. Taylor, et al., p. 77.

11. Margaret Lane, The Tale of Beatrix Potter (London and New York, Frederick Warne & Co., 1946) p. 138.

12. Jane Crowell Morse, ed., Beatrix Potter’s Americans: Selected Letters, (Boston, The Horn Book, Inc., 1982) p. xi.

13. Eli Siegel, Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism (New York: Definition Press, 1981) p. 149.

14. Eli Siegel, Aesthetic Realism Class of February 8, 1974.

15. Eli Siegel, Self and World: An Explanation of Aesthetic Realism (New York: Definition Press, 1981) p. 149.

16. Lane, p. 118.

17. Beatrix Potter, The Tale of Peter Rabbit (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1902, 1987, 1989) p. 9.

18. Ibid., p. 10.

19. Ibid., p. 18.

20. Ibid., p. 29.

21. Ibid., p. 30.

22. Ibid., p. 49.

23. Ibid.

24. Siegel, p. 146.