Dear Unknown Friends:

We are serializing the historic 1956 lecture How Aesthetic Realism Sees Art, by Eli Siegel. In it, he shows stirringly, logically, with ease, scholarship, sometimes humor, that all art “is the oneness of the permanent opposites in reality as seen by an individual.” This talk is mainly about the visual arts. Many of the people attending it were working artists, and a pair of opposites Mr. Siegel speaks of throughout are those very technical opposites outline and color. They are, he shows, phases of another pair of opposites, which are technical too but also everyday, and are present in the state of mind of everyone: within and without. Our life is a drama, sometimes tumultuous, of what we see as within ourselves—our thoughts, our feelings—and a world we see as outside ourselves.

In the part of the talk included here, Mr. Siegel also comments on something which, at the time, it was fashionable to put forth with a certain triumph, smugness, even belligerence: that “You can’t explain beauty!” I love the way Mr. Siegel discusses that notion. Today it is not asserted so much; yet it is a notion had by millions of people. I have felt impelled to write a little about it here, because something like it is affecting America gigantically at this time.

Beauty & Truth

Whether or not a person says outwardly, “No one can explain what’s beautiful,” there is an assumption most people act on which is tantamount to that. The assumption is, “Critics can say things, but beauty is pretty much what I take it to be.” This viewpoint is in the phrase “Beauty is in the eye of the beholder.” It’s in the phrase “I don’t know much about art but I know what I like.” It may not seem terrible to assume that nothing definitive can be said about beauty; yet that state of mind has a likeness to the little expressed but widely had feeling about truth—“No one can tell me what truth is: truth is what I want it to be.”

The making what one desires, what pleases oneself, constitute what truth is, is taking place on a massive scale in America now. The truth about an election, about ballots, about vaccines, about a vicious assault against the US Capitol, has been made something one doesn’t have to see as existing: the truth about these and more can be made into something to suit oneself, one’s conceit, and one’s purposes.

There is an all-important difference between persons’ not knowing what constitutes beauty and their saying that therefore beauty cannot be defined. In fact, every important art critic has gone on the idea that the distinction between something beautiful and something not beautiful is real, even as one may not know enough to say fully what that distinction is. Every important critic (even a so-called “subjective” critic like Pater) has gone on the belief that there is such a thing as definite beauty and has tried to ascertain in some way what it is.

If beauty cannot be explained, if nothing true can be said about it, art of course is insulted; it’s up for grabs: you may as well say what quite a few people feel—that their nephew’s painting is as good as Mondrian’s. But also, if beauty cannot be explained, and distinguished from what’s not it, then we as people are sunk, because that would mean there’s no way of distinguishing between a beautiful, just emotion and an ugly, unjust emotion.

People don’t know, for instance, what is a beautiful way of seeing a person, feeling about a person. Yet the idea that they’ll never know what a beautiful way of seeing and feeling is, because it can’t be defined—that would be desolating. Aesthetic Realism, however, explains that beauty as the oneness of opposites is about us too and is what we thirst to have in our own feelings and purposes. A woman thinking of her husband, for instance, wants to see him in a way that puts together exactitude and wonder. Her need is to try to know him, not sum him up, but see him truly—as composed of thousands of facts and as related to thousands of things, happenings, persons—and through that accurate knowing, feel his mystery.

Beauty Defined—& a Poem

I have seen, through careful critical looking, that what makes a thing or person or action beautiful not only can be explained, but has been explained—by Eli Siegel. “All beauty,” he wrote, “is a making one of opposites, and the making one of opposites is what we are going after in ourselves.” The magnificent philosophy and education which is Aesthetic Realism is based on that explanation.

As we approach the discussion by Mr. Siegel that you’ll soon read, I have thought it right to use, as prelude, something that seems quite different from it: a poem about a trouble within people. Eli Siegel wrote “The Dark That Was Is Here” in 1953. It was published the next year in the Antioch Review, then in 1957 in his book Hot Afternoons Have Been in Montana: Poems. Following it, I’ll comment a little on its relation to the lecture we’re serializing.

The Dark That Was Is Here

A girl, in ancient Greece,

Be sure, had no more peace

Than one in Idaho.

To feel and yet to know

Was hard in Athens, too.

I’m sure confusion grew

In Nika’s mind as she,

While wanting to be free,

Hoped deeply to adore

Someone; and so no more

Be wretched and alone.

—Ah, hear the keen, wise moan

Of wind at twilight, past

Old trees, which darken fast.

That wind was heard, that blur

Of trees was seen by her

Of Attica.—The sound

Of wind on dry, cool ground

Once more is heard by girl,

With heart in autumn whirl.

The trees stand up in grey;

It is their ancient way—

All this in Idaho,

Where grieving girls now go

In mingled love and fear.

The dark that was is here.

The poem is about two big opposites that are in people, which can seem so separate, painfully separate, from each other: knowing and feeling. The trouble about them is told of succinctly, yet throbbingly, and with musical width, in these two lines: “To feel and yet to know / Was hard in Athens, too.” Those human opposites of feeling and knowing have a relation to the technical art opposites Mr. Siegel speaks of in the lecture, outline and color. Knowing seems to be a more delineating thing, defining thing—like line. Our feeling can seem, like color, to be, of itself, without shape—and to be looking for a shape that line can provide.

Meanwhile, feeling and knowing are one in all art. A true artist in any field has emotion that’s large, deep, wide. Yet it is together with a tremendous desire to see exactly, to comprehend. And these, feeling and knowing, the poem says, are the very opposites that have mixed people up so much as to love.

This is a great poem. The thirteen three-beat couplets are tight, with their concision and rhyme—and yet the statements and feeling in those couplets seem to reach and overflow and go beyond, even as they are gracefully and firmly contained.

We have difference and sameness. In this poem, two people, of different times, different places, are shown to be akin. And we have the opposites always with each of us—self and world: the earth, with its trees and wind and ground and sky, comments on the feeling of a young woman of once and one of now.

I love the line “The trees stand up in grey.” There is pride in that verticality of the standing trees, even as there is greyness. I think that the grey, and the “dark” told of in the poem, represent the confusion, the not knowing what to do with the opposites in oneself. And the poem gives each of the two young women a dignity in her confusion.

So this poem is art, high art. I have commented a little on it as standing for the opposites in people—and as having, in its technique, the opposites that are one in beauty itself.

—Ellen Reiss, Aesthetic Realism

Chairman of Education

The Explainable Mystery

By Eli Siegel

Note. Mr. Siegel has been discussing passages from De Arte Graphica, by Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy (1611-68), translated by William Mason.

In the Fresnoy poem there is something related to a question that has been brought up about the Aesthetic Realism way of seeing art: The opposites—is that all? But they will not explain beauty!—isn’t there something about art that nothing in this world can explain? And the opposites say: Sure—because the unknown is related to the known. That is part of philosophy. It’s hard to talk about, but we should see that an academician like Fresnoy brings up the matter. He is going to give rules, but he says, even so, there is something about beauty that nothing can explain.

Now, I simply love the unexplainable; I am a terrific romantic. But I do say that the unexplainable exists just as much as the explainable; that what you don’t know exists just as surely as what you do know. And when you say that you don’t know something, you’re already saying something you do know. That belongs to logic.

Still, it has been felt for a long time that there was something hard to explain about beauty. Dryden has a note, which I’m not going to read now, on this passage of Fresnoy, and he shows that the Roman critic Quintilian also said that in poetry and art there is something no one can talk about. Now we have Fresnoy:

Hear then the Muse; tho’ perfect beauty towers

Above the reach of her descriptive powers,

Yet will she strive some leading rules to draw

From sovereign Nature’s universal law.

So we have this contradiction. On the one hand, people have said, You can’t explain beauty—nothing can be said about it! But on the other hand, they do try to say a few things. The explainable and the unexplainable are opposites, and their relationship is something Aesthetic Realism does not avoid. The problem is invited. What is the relation of the mysterious to the plausible, the understandable, the acceptable? That is a specific question, as much a specific question as What should you do with the pepper now that you have the salt? But it has most often been dealt with in this way: there is something unexplainable, so let’s stop trying to know; let’s enjoy, let’s be rapturous and forget logic! With most people, logic has been seen as making for the absence of rapture, which is a dull, false idea. There is no real rapture in this world that doesn’t say to logic, Hello! I like you. The feeling that logic is that which desiccates and that which introduces a drab element, has been the result of a constant fear of it, and misuse.

Rules & Je Ne Sais Quoi

But what I am trying to point out for the moment is the following: this 17th-century academician, Fresnoy, does say that in art there is a je ne sais quoi, a something unknown. And we find that that statement is still of the moment. Let us take a statement from the cubist Georges Braque, included in his “Pensées sur l’art” (“Thoughts about Art”). I’m reading from a magazine, Confluences, of 1945, just after the Resistance became the persistence in France. We find Braque saying the same thing as Fresnoy, and bringing together the unknown and known. I’m translating:

There’s only one thing in art that is worth anything: that which one cannot explain.

Very good. But then Braque says in another of these pensées the same thing as Fresnoy: Fresnoy said, There is something you cannot explain, yet I’ll give you a few rules that will console you. And Braque says it:

I love the rule which corrects emotion.

So what have the two, rule and what one cannot explain, to do with each other?

Then there is a third statement of Braque, which goes along with all the idealism in the centuries: that when thought goes into matter, it becomes more spiritual. Braque puts it in the language of 1945:

The true materialist, the more he goes into matter, the more he exalts spirituality.

That is the making one of opposites: the more you see matter, the more it becomes spirit!

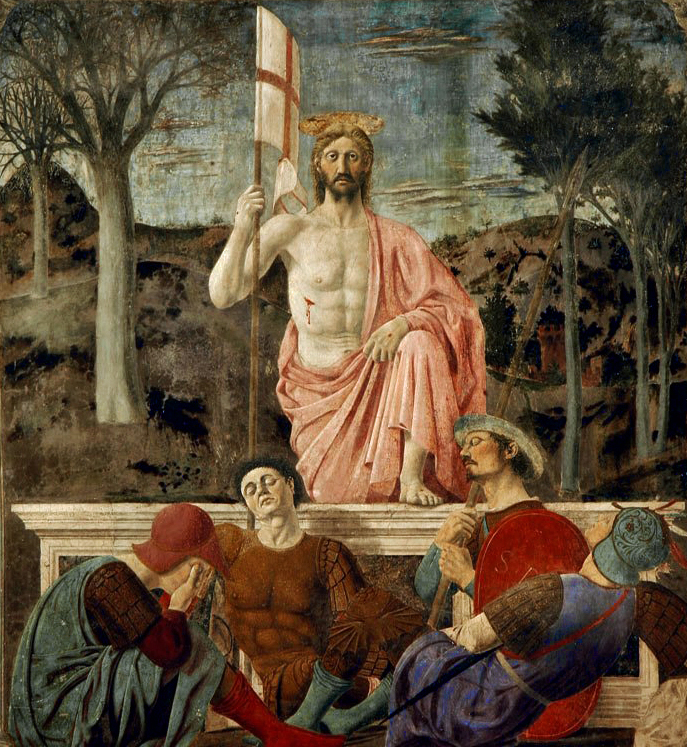

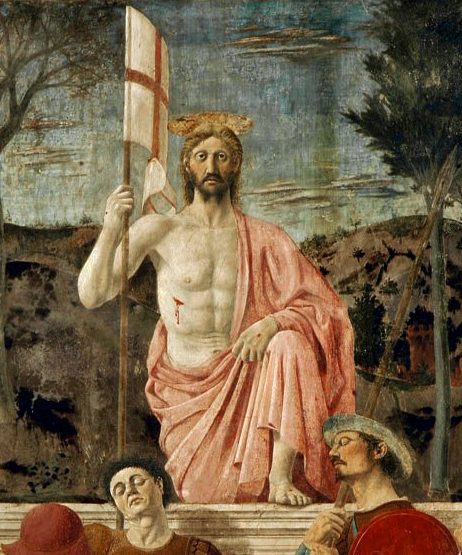

Outline & Color: Piero della Francesca

I go to 1901 or so. What I’ll read is about a painting that was discussed by Dorothy Koppelman, a painting I see as one of the great ones. I’ve thought it quite funny but still see it as great: what’s funny can still be most mattering. The opposites we’ve been looking at, outline and color, without and within, we have in a particular way in Piero della Francesca.

It is thought that Piero della Francesca was severe, rigid, given to a certain logical structure in his work. He is. But in his way he had the problem of line and color. The best thing in the book I’ll read from, Piero della Francesca, by W.G. Waters, is the description of The Resurrection. Here, we find the problem brought up in terms of one artist in what I think is his best work: The Resurrection of Christ, in Borgo San Sepolcro. We have a relation of without and within. It is a very big relation. There is nothing deeper in this world than out and in, the margin and the withinness. Waters writes:

The sprawling forms of the soldiers, the ragged trees, the amorphous hills in the background, and beyond all those terrible eyes of the central figure fixed in their sockets and overpowering all else in the composition by their stony regard, provoke no thrill at the consciousness of beauty revealed; nay, there may very likely surge up a sense of revulsion and disappointment.

The accent is on the outline: the “amorphous hills,” the fairly bleak trees; then lines of an arm, lines of a banner, lines of soldiers. Another passage:

In composition it is extremely simple. The figures fall naturally into triangular form, and indicate the geometrical training of his hand and eye.

Here we come to why Piero della Francesca is very much of the present century: because he put together geometry and emotion. And this is what we want. We want the feeling that our blood cells have something to do with the eternal forms. If we could only relate our palpitating worries, fearful body, to something as eternal as a triangle and a sphere, it would be a comfort. So Waters is aware of “the geometrical training of [Piero’s] hand and eye.”

Then there is the tomb. Here we have color—and another putting together of opposites. There is a tomb, but Christ is in a pink robe. Isn’t it wonderful to think that death has to do with pink? I think that’s worth a lot:

The tomb, classic in design and made of marble, stretches almost across the picture, and from it rises Christ, partially clad in a pink robe and bearing in his hand a flagstaff.

To have somebody come out of a tomb not in white but in pink, that’s something. And further:

His left foot rests upon the edge of the tomb, and is a most exquisite piece of drawing.

So we have that word which is used against color: drawing (others are draftsmanship, figure, design). Then there is color:

The sky is streaked with clouds, reddened by the rays of the ascending sun, and begins itself to glow with the saffron tint of dawn on Christ’s left hand. On this same side, the side of the rising sun and of rekindling life, the trees are green and full of leaf, while on the opposite one they are bare and dead.

Whatever else, we have a putting together of cold and warm. We have bleakness and effulgence. We have kindness and desolation. And in the long run we also have humor and the greatest seriousness. —Another passage:

The chief attribute of the figure of Christ, taken by itself, is an expression of irresistible force. This perfectly developed organism, this splendid and robust manifestation of muscular strength, rises from the tomb to bring salvation and liberty to the world, and we feel, as we contemplate, that any effort to resist the calm onward sweep would be vain.

That appeared in 1901. Today, there is still the problem of line and color. And we are seeing it expand.

What They Have Gone For

In my coming to Aesthetic Realism, I found that what artists have gone after for years is the seeing of the world in a way that would make them proud of themselves; and for that, the world has to be accepted in its contraries.