By Eli Siegel

Dear Unknown Friends:

There are two deep, permanent purposes in man: one, is to be pleased or happy; two, is to organize this desire to be pleased or happy so that it takes in a sight of the world. A boy may be pleased by the lively whirling of a butterfly in a New England summer morning. The pleasure is there. However, when later the boy sees how a butterfly’s wing has a structure enabling it to play with the sun, the earlier pleasure has become more organized. Both aesthetics and science are the affirmation of immediate, pleasing sensation. We get a pleasure seeing how a pebble is made which, while it includes the earlier pleasure of seeing it quietly among green grass, has the pleasure from seeing structure as life, from composition as representing reality.

Aesthetic Realism sees the purpose of art as, from the beginning, the liking of the world more.

This Is Asked

What is art for?—

To like the world more,

To like ourselves more,

To like time more.

It is well to look at an American history of world art to ascertain whether art puts into action the deepest desire of man, with that desire being to like the world.

1. Helen Gardner, Chicago

If any woman gave her life to the understanding of art in all its forms and in all its historical modes, it was Helen Gardner, Professor, in 1936, of the History of Art in the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Miss Gardner’s mighty work, Art Through the Ages (Revised Edition, Harcourt, Brace, 1936), tells carefully of Etruscan art, medieval Russian art, and certainly the art of Renaissance Italy; tells of the art of the American Indian and of United States art.

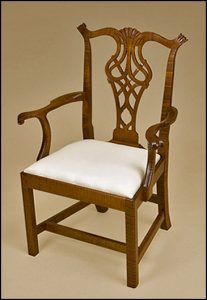

In Miss Gardner’s book, art unifies the world. A Navaho Blanket (page 556) mingles in time and possibility with a Chippendale Chair (page 498).

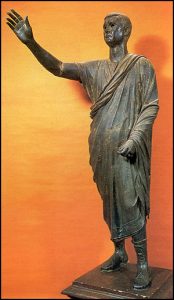

A “Young Maize God” of Copán (page 543) joins (page 183) with a stately classical orator in bronze of perhaps the 4th century B.C.

An archer of long ago (page 139) joins with a little Concert by the 17th-century Ter Borch of Holland (page 485).

One can get the idea from the historical art-things which I have mentioned that beauty or art is as wide as reality. There is no reality which is not beautiful in some fashion. This means that before an artist, say, looked at a dried leaf or a rusty spoon to see the beauty there, the dried leaf and rusty spoon were saying something good themselves. Reality is its own praise. Facts are their own gloria in excelsis.

Again, to Miss Gardner. Miss Gardner tells patiently of the going towards beauty of paleolithic or neolithic man. Man’s desire to like the world is in these words of Miss Gardner (Art Through the Ages, page 3):

Here may we not recognize that of two flints which cut equally well one is more pleasing than the other because of a quality in the form that has nothing to do with the utility of the tool yet unmistakably enhances the object to the eye.

From this we can gather that ancient man had art thoughts. As soon as we like one dish of food rather than another because the first dish has been arranged better, we are giving homage to the world as possibly graceful. This is what man of long ago did when he felt that in his southern European cave, he could add something honest to the being of an animal he had met earlier.

And we find in Miss Gardner’s work that art always had the tendency to make a one of seeing individual and world. Miss Gardner tells us this on page iv:

A work of art is, on the one hand, a social document, and expression of varying life conditions. It is, on the other hand, an individual visual form.

On page 3, Miss Gardner tells us that in a hot climate—”an energy-consuming climate”—something unconscious was working in behalf of the meaning of art. More was in the unconscious of paleolithic man than Freud saw. Miss Gardner says:

Even in the face of an energy-consuming climate, then, latent impulses that are fundamental in the arts were finding expression.

Ancient art showed a desire to like the world by making the inert and the moving one; sameness and difference one. To show that these permanent aspects of reality can work together is a way of liking the world. Miss Gardner, writing of Stonehenge (page 14), uses the words “order and symmetry” and “large and small concentric circles.” But what she is doing is presenting early existence as orderly and mobile. Miss Gardner, writing of the pillars, the curves, the horizontals of Stonehenge, says:

Ancient art showed a desire to like the world by making the inert and the moving one; sameness and difference one. To show that these permanent aspects of reality can work together is a way of liking the world. Miss Gardner, writing of Stonehenge (page 14), uses the words “order and symmetry” and “large and small concentric circles.” But what she is doing is presenting early existence as orderly and mobile. Miss Gardner, writing of the pillars, the curves, the horizontals of Stonehenge, says:

In the arrangement there is a feeling for order and symmetry, and a rhythm that is varied by alternating the large and small concentric circles.

Miss Gardner’s prose itself sometimes goes along with reality as a commingling of hubbub and indolence. This sentence of our historian (page 18) is like some lines from Leigh Hunt’s famous sonnet, “The Nile.” Here is Miss Gardner in a sentence of sleepy activity:

Miss Gardner’s prose itself sometimes goes along with reality as a commingling of hubbub and indolence. This sentence of our historian (page 18) is like some lines from Leigh Hunt’s famous sonnet, “The Nile.” Here is Miss Gardner in a sentence of sleepy activity:

Then, with a change of climate in northern Africa which brought about desert conditions, Stone Age man and the animals gathered about the oases or migrated to the abundant waters of the Nile Valley.

2. Leigh Hunt Is Present

Aesthetic Realism says we praise the world by showing the world as motion and stillness. The making one of opposites is the deepest way of praising the work of the Lord; it is the most sincere way. In his sonnet, “The Nile,” Leigh Hunt extols the makeup of the world by showing it as motion and quiet. Here are lines from the poem of 1818:

It flows through old hush’d Egypt and its sands,

Like some grave mighty thought threading a dream,

The laughing queen that caught the world’s great hands.

As Leigh Hunt brings the vivacious Cleopatra to the stately Nile, he is merging Egypt as restrained and Egypt as brisk. The sculpture of a fetching girl can bring about permanent stillness and engaging liveliness.

Later, Leigh Hunt presents silence as a great, somewhat startling occurrence:

Then comes a mightier silence, stern and strong.

Following this, life is presented as customary patter and ripple—which it is:

And hear the fruitful stream lapsing along

‘Twixt villages.

3. The World Twisted and Straight

That man wanted to make a world that was attractively twisted and straight is to be seen in the old Greek approaches to the column. Look (Art Through the Ages, page 130) at “The Upper Part of a Column from the Eastern Porch of the Erechtheum.” There is such a desire on the part of the artist of years ago to be simple; also ornate. Lines go up and down; they revolve into themselves, too. And little decorative effects defy the severity of the Hellenic vertical.

That man wanted to make a world that was attractively twisted and straight is to be seen in the old Greek approaches to the column. Look (Art Through the Ages, page 130) at “The Upper Part of a Column from the Eastern Porch of the Erechtheum.” There is such a desire on the part of the artist of years ago to be simple; also ornate. Lines go up and down; they revolve into themselves, too. And little decorative effects defy the severity of the Hellenic vertical.

The world may start with something complicated or confusing; it may start with the unabashed, wide simplicity of a summer sky. On page 168, we have a chance to look at things having some Peloponnesian diversity. The “Corinthian Capital from Epidaurus” presents entanglement first. As one looks, however, the stately vertical is perceivable. There is also a solemn circularity. The horizontal is above all, accompanied by a touch of the curved and diagonal. The Corinthian Capital, then, is a study in the network and oneness of the world.

The world may start with something complicated or confusing; it may start with the unabashed, wide simplicity of a summer sky. On page 168, we have a chance to look at things having some Peloponnesian diversity. The “Corinthian Capital from Epidaurus” presents entanglement first. As one looks, however, the stately vertical is perceivable. There is also a solemn circularity. The horizontal is above all, accompanied by a touch of the curved and diagonal. The Corinthian Capital, then, is a study in the network and oneness of the world.

4. Manyness and Oneness

There are two ways of liking the world through art. One is the way of the Persian rug: to show the world as many, unexpected. It was the way of the Corinthian column of a while ago. We know that the Hindu gods and goddesses were presented as multitudinous. It was felt that seeing divinity as many honored that divinity. The praise of God and the world through manyness is in Buddhist art, in Byzantine art, in Mexican art, and in various aspects of Christian art.

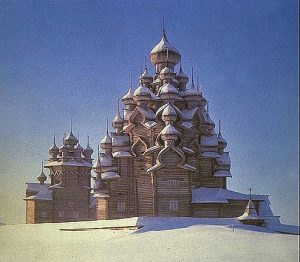

On page 240 of Miss Gardner’s work, a church shows the sacred as one and many, unified and various. On the same page, another church presents the sacred with “oriental lavishness.”

5. Up and Down

The world is down and up, and much of art is given to showing how the world as both down and up is worthy of our like. An engaging example of the world likable because it is down and up at once is on page 271 of Miss Gardner’s work: “Equestrian Portrait of a Prince and His Servant.” This study in down and up is of Persia. The prince does not seem excessively exalted because he is riding and flying on a black, delicate horse.

The world is down and up, and much of art is given to showing how the world as both down and up is worthy of our like. An engaging example of the world likable because it is down and up at once is on page 271 of Miss Gardner’s work: “Equestrian Portrait of a Prince and His Servant.” This study in down and up is of Persia. The prince does not seem excessively exalted because he is riding and flying on a black, delicate horse.

The world is deep; and depth has in it the ideas of both loftiness and profundity. In man’s unconscious, the world seen as down and up is a world that can be more clearly liked. What I have just said is discernible on page 295 of Miss Gardner’s work: “Stave Church of Gol. 1000-1500. Near Oslo.” The sloping surfaces of this church are reality going down and reality going up. A deep roof of the old New York kind would give one simultaneously a feeling of height and descent. A tall stairway can do this.

The world is deep; and depth has in it the ideas of both loftiness and profundity. In man’s unconscious, the world seen as down and up is a world that can be more clearly liked. What I have just said is discernible on page 295 of Miss Gardner’s work: “Stave Church of Gol. 1000-1500. Near Oslo.” The sloping surfaces of this church are reality going down and reality going up. A deep roof of the old New York kind would give one simultaneously a feeling of height and descent. A tall stairway can do this.

Perhaps the most noted example of down and up in art is the cathedral of Notre Dame at Chartres. This cathedral has spires; and spires have loftiness and lowness. The spires are at the sides of the cathedral; the middle is lower.

Sometimes in art, height seems to go somewhat wild. An instance of this wildness is on page 312 of Miss Gardner’s work: “Chartres. Western Portal: Kings and Queens.” These elongated and raised medieval representatives of royalty should be thought of in relation to dead recumbent royalty in other medieval sculpture.

The wings of the “Smiling Angel” of Reims (page 320) seem to make her higher and lower at once. How can wings be of much use plumply in a cathedral? The sculpture satisfies man’s sense of flight and also his desire to stay where he is.

6. Brightness and Grace

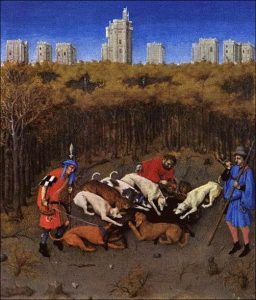

The medieval illuminations and paintings satisfy man’s desire for the bright and also the sedate. Sedateness and vividness are in A Book of Hours (Gardner, page 328). And the famous tapestry of the 16th century, The Lady and the Unicorn ( Gardner, page 332) is a study in brightness and grace, too. Tapestry itself was often brightness and luxurious thickness.

7. Continuity and Stop

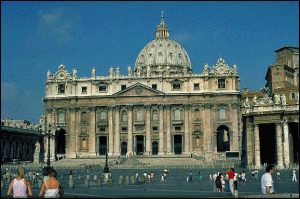

The world goes on as an accomplice of infinity; and it stops. The desire to see the world as continuous—stopping nevertheless—is in the “Carving from the Ducal Palace, Urbino,” page 341. The world as going on is on page 348 of Gardner ‘s work: “St. Peter’s Cathedral, Rome.” Something’s here that does not have clear termination. A great representation of the world continuous and stopping is Donatello’s “Cantoria, or Singing Gallery.” One can feel keenly Donatello’s desire to say what is going on here can go on tomorrow, too; and later. That this work of Donatello stands for the world’s going on and halting is in these words of the historian (page 361):

But these figures, not withstanding their riotous activity, are confined within regulated planes of depth and their movements are both controlled and emphasized by the framework with its static classical motives.

8. Pathos and Satisfaction

The greatest way art has of encouraging the desire to like the world is to have pathos and satisfaction one. As I mention this, I am with the world that has in it all the feelings of man in the years. The “Bound Slave” of Michelangelo is on page 367 of Gardner ‘s Art Through the Ages. Here we have the strength of man made one with the compassion he deserves. Strength and compassion are much in art and are a means of liking the world.

The greatest way art has of encouraging the desire to like the world is to have pathos and satisfaction one. As I mention this, I am with the world that has in it all the feelings of man in the years. The “Bound Slave” of Michelangelo is on page 367 of Gardner ‘s Art Through the Ages. Here we have the strength of man made one with the compassion he deserves. Strength and compassion are much in art and are a means of liking the world.